Minding your Ps and Qs

Guernsey McPearson

Poor old Harvey Puffer is in quite a state. Somebody was stupid enough to ask him to go along to a neighbourhood school to talk to the 6th formers about the pharmaceutical industry. They had all been reading Poison Pills by Jerry Copperfield and he got some pretty aggressive questions. Things weren’t helped by the fact that he had to confess that he hadn’t read the book. There is nothing quite as self-righteous as sixth-formers and by the time he escaped he had been accused of not only of poisoning The Third World but of causing global warming. (The former was rather unfair as Harvey wouldn’t hurt a fly, on the other hand, he is a great producer of hot air.)

I caught up with him a few days later when he came to see me in my office. By now he had a well-thumbed copy of Poison Pills.

‘Look at this, Guernsey,’ he said, ‘It makes depressing reading. Apparently it’s all our fault. Authors are not publishing negative studies. The pharmaceutical industry are particularly bad. He even provides proof that journals don’t have a prejudice against negative studies.’

‘Oh,’ I said, ‘what proof would that be?’

‘It’s all here,’ he said, ’a number of studies have compared the acceptance rates of submitted negative and positive studies and they find no difference. There is even an Archie Association meta-analysis that summarises them all and there is no difference.’

‘So is there is a prejudice,’ I said.

‘Didn’t you hear what I said? There is no difference in acceptance rates.’

‘My point exactly.’

‘You are going to have to explain,’ said Harvey, ‘You are being bloody mysterious in your usual way.’

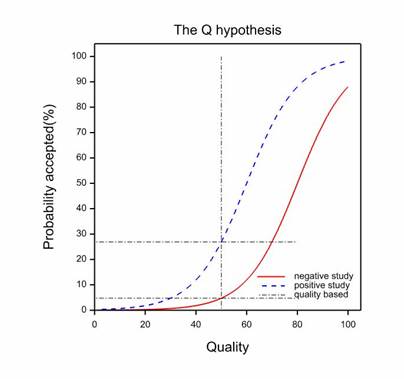

‘Bear with me,’ I said. My office is pretty chaotic and I was looking for some board-markers. ‘Aha,’ I said, waving a red, a black and a blue one in triumph. I then proceeded to draw something like the figure below on the board. (Although obviously not as pretty as what you have here.)

‘You are going to have to explain this to me,’ said Harvey.

‘Well the X axis (that’s the horizontal scale, Harvey) is supposed to represent quality.’

‘You can’t measure quality,’ said Harvey.

‘Great,’ I said, ‘let’s do away with peer-review altogether.’

‘You can’t do that,’ said Harvey, in shocked tones, ‘the quality of stuff that got published would be terrible.’

I rolled my eyeballs. ‘Oh, I see,’ said Harvey, ‘well, OK in some sort of a sense I suppose one can get a feel for quality.’

‘The graph is supposed to be conceptual, Harvey. If you can distinguish between papers and say that some of them are better than others, then you ought to be able to order them roughly on the horizontal axis. That horizontal axis is supposed to be some sort of a rough and ready quality scale along which you can place papers. Let’s suppose is runs arbitrarily from 0 to 100.’

‘OK. But where is this leading?’

‘Well Y axis (that’s the vertical scale, Harvey) is supposed to represent probability (in percent) of getting published if submitted. The curves I have drawn show that the probability of being published for studies of the same quality is very different according to type of study. In fact I have drawn in a possible quality threshold as the vertical dashed line her and you can see that the probability of acceptance is very much higher for positives studies than for negative ones’

‘Aha,’ said Harvey triumphantly, ‘you weren’t listening. The curves should be identical. We know that is so because the probability of being published is the same. The Archie Association analysis shows it. That must mean that the curves are identical.’

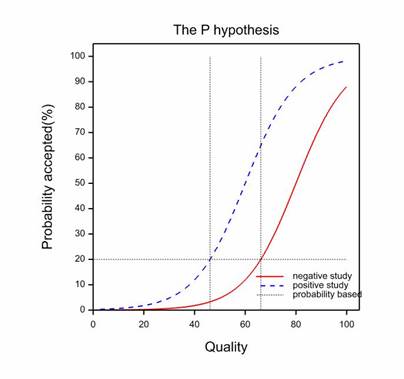

‘Must it?’ I said. ‘You seem to assume that authors make a decision based on quality alone as to whether to submit and also, for that matter, that the quality of negative and positive papers is the same. We can call this the Q hypothesis. However, suppose that they make a decision to submit based on probability. We can call this the P hypothesis. Then we might have a situation like this.’ I erased the previous dashed lines and drew a horizontal line intersecting both curves. ‘Now the probability is the same for papers just reaching the threshold at which authors will bother to submit them but the quality of negative studies is much higher.’

‘Hang on a minute,’ said Harvey. ‘How would the authors know anything about the probability of acceptance of submitted papers?’

‘Well, Harvey, I believe you have had papers published in APE (The Albion Physician’s Enquirer), The Speculum and JAM (The Journal of Appalachian Medicine).

‘Well. Only once in JAM’, said Harvey putting on an expression in which pride could be detected shining through a thin veneer of humility.

‘Well, do you ever review for those journals?’

‘Yes, of course, I review for them regularly.’

‘Well don’t you think it is a bit odd that the Copperfield hypothesis requires you to be an authorial sinner, with a prejudice against negative papers and a reviewing saint with none whatsoever? How do you manage this Jekyll and Hyde trick? You would have to think much more poorly of your own negative papers than you do of those of your colleagues.’

Harvey was about to say something and then stopped. You could almost hear the cogs turning.

‘You look nonplussed. Or should that be nonminussed.’ I said, ‘Now the important thing would be whether negative and positive studies differed in quality. If the P hypothesis were true we should expect the submitted negative studies to be higher in quality than positive studies but have the same probability of acceptance. You can see that exactly the same curves as before would lead to quite different evidence being seen.’

‘Well is there any evidence of this?’ Said Harvey.

I got my copy of Poison Pills from the fiction section of my bookshelves. ‘Well’ I said,’ this cited article caught my eye. It’s from JAB (Joints and Bones) and it has a rather interesting title. “Negative studies are just as likely to be published as positive ones but their quality is better”. I find that rather intriguing don’t you? I would have thought that anybody interested in understanding the problem would have looked at this rather carefully and perhaps even read it. But it is one thing to cite and another to read. When one actually gets as far as to skim the abstract one discovers that the authors found highly significant difference in quality between negative and positive studies in favour of the former.’

‘Gosh,’ said Harvey, ’I see now. Copperfield has actually misunderstood. How did he manage to overlook the evidence about quality? You would think that ought to have struck him.’

‘Well’, I said, ‘as a medical journalist he is, of course, a member of a subset of a profession that has great trouble understanding evidence.’

‘Ah,’ nodded Harvey wisely, ‘yes, that is a problem with journalists.’

‘True,’ I replied, ‘but it wasn’t journalists I was thinking of.’